Long before turkey and all the trimmings took centre stage, our ancestors roasted whatever they could catch. From Saturnalia to steaming puddings, the Christmas table has evolved with every century. So how did we trade wild boar for turkey, and when did we turn the simple spud into roastie royalty. Let’s carve into the delicious history behind our favourite festive meal.

Season’s Eatings: Neolithic Feasts

With Christmas thousands of years away, Neolithic communities across Britain and northern Europe marked the turning of the year with great feasts tied to the winter solstice. The harvest was stored away, animals that couldn’t be fed through the cold months were eaten, and the return of the sun and the cycles of nature were prayed for.

Archaeological finds from sites like Durrington Walls near Stonehenge reveal vast gatherings for these midwinter feasts. Animal bones - mostly pig and cattle - show that they were roasted over open fires, while charred barley grains and traces of mead or ale suggest their meal was as communal and enjoyable as it was ceremonial. Historians believe these get-togethers were a far cry from quiet family meals. They were, for all intents and purposes, parties, with blazing bonfires and people sharing food and drink.

Saturnalia and the Feast Before Christmas

As the centuries rolled on, midwinter merriment found new meaning in the world of ancient Rome. Saturnalia, held in honour of the god Saturn, was the high point of the Roman calendar - a week-long festival of mischief, revelry, generosity, and abundant food held between the 17th and 23rd of December. During Saturnalia, gifts were exchanged, and homes glowed with greenery, candles, and song. Social norms also flipped, with slaves being served by their masters, but just for a brief time!

Even two thousand years ago or more, the Roman Saturnalia table wouldn’t look out of place today. It groaned under the weight of roasted meats, sausages, olives, figs, nuts, honey cakes and plenty of wine. For the elite, whole pigs or boars took pride of place, glazed with honey or fruits and surrounded by exotic ingredients brought from across the empire. In humbler homes, the food was simpler, and included bread dipped in oil, stews thickened with beans and vegetables, all washed down with cheap and cheerful wine.

From Faith to Feast: Early Christian and Medieval Christmas Tables

Early believers didn’t abandon winter feasting when Christianity took root across Europe, they simply reimagined it. By the fourth century, Christmas had been fixed near the old solstice festivals, and while Saturnalia may have influenced early celebrations of Christ’s birth, the table remained central to both.

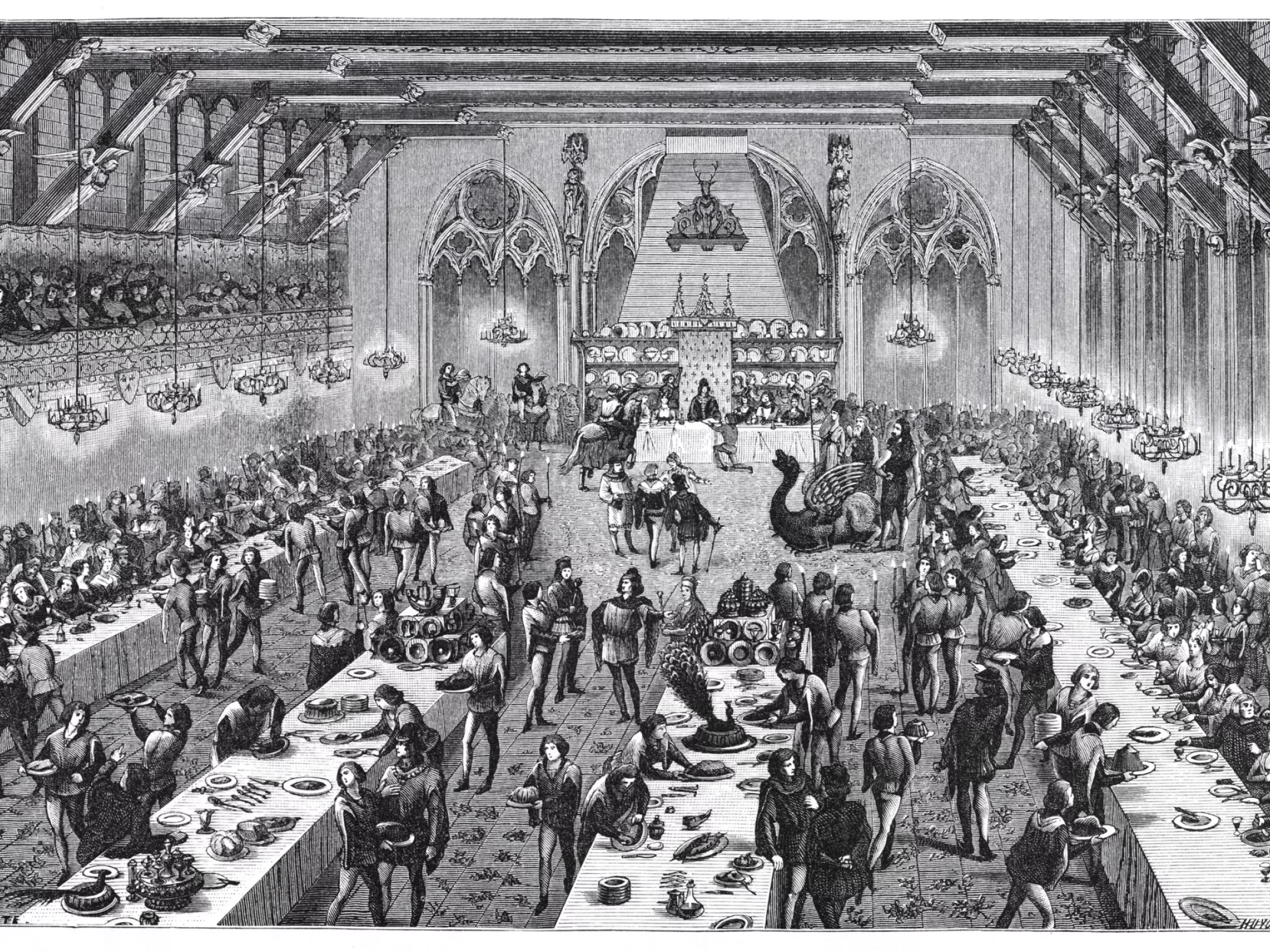

In early medieval Britain, Christmas was a season rather than just a day, and involved twelve days of food, faith and festivity. Wealthy families threw lavish banquets in their great halls, with meat at the heart of it all, including boar’s head, venison, goose, and peacock roasted over open flames and often glazed with fruit. For a privileged few, rare and expensive spices imported from the East were used to flavour pies and puddings.

For humbler families, Christmas was simpler rather than lavish. Leftovers from the lord of the manor might be shared out, and communal meals still brought people together. Pottage - a thick soup or stew made from whatever was to hand, usually vegetables, grains and herbs, sometimes with meat or fish - along with bread and ale, was common fare for people all across the country.

The Tudors: A Feast For A King

By the sixteenth century, the Christmas feast had become a spectacle of status and abundance. Indeed, the Tudor era is where Christmas really starts to look recognisably ‘traditional’. Famously, no-one feasted quite like King Henry VIII, who was among the first English monarchs to serve turkey at Christmas. Before that, roasted goose, boar’s head, and venison reigned supreme.

The Tudor table became a sumptuous blend of old tradition and global influence, and banquets at court were elaborate performances. A Christmas dinner in aristocratic houses, palaces and castles might begin with game pies decorated with pastry crests, followed by dishes such as swan, crane, badger, or a whole boar presented with gilded tusks. Servants carried dishes in grand procession to impress guests and showcase royal splendour. Among the sweet offerings, mince pies held special symbolic power - originally made with minced meat, suet, fruits, and exotic spices that represented the gifts of the Three Wise Men, a reminder that this was a religious festival, not just a convenient excuse for excess and indulgence.

Beyond the royal court, the Tudor Christmas was a time for generosity. Households large and small gathered for shared feasts. The day mixed faith and festivity, creating a pattern we still recognise today, twelve (or sometimes more!) days of food, fellowship, and cheerful excess.

From the Georgians to the Victorians: Tradition on the Table

By the eighteenth century, Britain’s Christmas table had grown more refined but no less hearty. The upper classes dined in style, with multi-course spreads which showcased wealth and culinary innovation. Goose was the popular choice for most families, while plum pudding, born from medieval pottage and the forerunner to Christmas pudding, began to sweeten the table. Meanwhile, new methods of roasting and baking helped turn the Christmas meal into something carefully curated rather than excessively indulgent. The festive menu was gradually taking form - roasted meats, puddings, fruit-laden pies, and plenty of punch to go around.

Then came the Victorians in the nineteenth century who didn’t just enjoy celebrating Christmas, they practically invented it as we know it today. In 1843, Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol redefined the holiday spirit and placed the family feast as its heart. Turkey, once a luxury, eventually became the table’s centrepiece towards the later years of Victoria’s reign. Its size made it perfect for shared dining and perhaps most crucially, as foreign trade increased, it was increasingly affordable. Alongside the bird came all the trimmings - roast potatoes, gravy, stuffing, and vegetables - the festive blueprint many still follow. The Victorians also codified the customs that shape the seasonal dining room, including Christmas cards, crackers, and puddings set alight with brandy.

From Rationing to Roasties: Twentieth Century Christmas

As the twentieth century unfolded, Christmas dinner weathered wars, rationing, and the rapid modernisation of British life. During the world wars, festive feasts were slimmed down, with poultry, sugar, and butter tightly rationed. Many families made do with what they had - rabbit or pork instead of turkey, bread puddings sweetened with dried fruit, and cakes enriched with mashed vegetables in an attempt to stretch ingredients as far as they could go.

Post-war prosperity brought turkey back in triumphant style. By the 1950s and ’60s, refrigeration, supermarkets, and new cooking appliances made the big bird more affordable and convenient, securing its crown as the centrepiece of the British Christmas table. The once-humble roast was now surrounded by all the trimmings - crispy potatoes, sage and onion stuffing, cranberry sauce, sprouts, gravy, and the ever-present Christmas pudding. In an age of broadcasting, cookbooks, and later, television specials, the Christmas dinner became a cultural event.

As the twentieth century came and went, the twenty-first blended tradition and nostalgia with convenience and variety. Ready-made everything lined shop shelves, while celebrity chefs revived heritage recipes and festive flair.

Full Circle: The Enduring Feast

From hunter-gatherers marking the solstice to today’s tables covered with crispy roasties, sprouts with pancetta, and lashings of Madagascan vanilla custard, every mouthful is an homage to what went before. Across the centuries, the ingredients and customs may have changed, but the heart of the feast remains the same.